Posts Tagged ‘progressPosts’

AquabrowserUX Final Project Post

Posted on: October 20, 2010

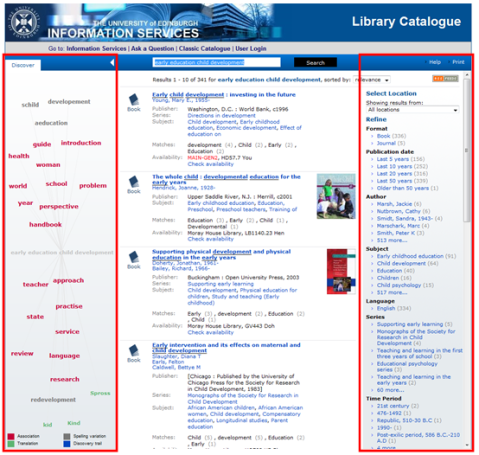

Screen shot of University of Edinburgh’s AquaBrowser with resource discovery services highlighted.

Background

The aim of the AquabrowserUX project was to evaluate the user experience of AquaBrowser at the University of Edinburgh (UoE). The AquaBrowser catalogue is a relatively new digital library service provided at UoE alongside the Classic catalogue provided via Voyager which has been established at the university for a number of years. A holistic evaluation was conducted throughout with a number of activities taking place. These included a contextual enquiry of library patrons within the library environment, stakeholder interviews for persona creation and usability testing.

Intended outcome(s)

The objectives of the project were three-fold:

- To undertake user research and persona development. Information gathered from the contextual enquiry and stakeholder interviews were used to create a set of personas which will benefit the project and the wider JISC community. The methodologies and processes used were fully documented in the project blog.

- To evaluate the usefulness of resource discovery services. Contextual enquiry was conducted to engage a broader base of users. The study determined the usefulness on site and off site which will provide a more in-depth understanding of usage and behavioural patterns.

- To evaluate the usability of resource discovery systems. Using the personas derived from the user research, typical end users were recruited to test the usability of the AquaBrowser interface. A report was published which discusses the findings and makes recommendations on how to improve the usability of UoE’s AquaBrowser.

The challenge

There were a number of logistical issues that arose after the project kicked off. It became apparent that none of the team members had significant experience in persona development. In addition, the external commitments of subcontracted team members meant that progress was slower than anticipated. A period of learning to research established methodologies and processes for conducting interviews and analysing data took place. Consequently the persona development took longer than anticipated which delayed the recruitment of participants for usability testing (Obj3). The delay also meant that participants would be recruited during the summer months when the university is traditionally much quieter. This was a potential risk to recruit during this time but did not end up being problematic to the project. However the extension of time spent gathering qualitative data meant that it was not possible to validate the segmentation with quantitative data. This was perhaps too ambitious for a project of this scale.

The challenge of conducting the contextual enquiry within the library was to find participants willing to be observed and interviewed afterwards. The timing once again made this difficult as it took place during exams. The majority of people in the library at that time were focussed on one task which was to revise for exams. This meant that persuading them to spend ten minutes talking to researchers was understandably difficult. In addition to this, the type of users that were common in the library at that time were limited to those revising and whose needs were specific to a task and did not necessarily represent their behaviour at other times of the year.

Ensuring that real use data and participation was captured during the contextual enquiry was also a challenge. Capturing natural behaviour in context is often difficult to achieve and carries a risk of influence from the researcher. For example, to observe students in the library ethically it is necessary to inform subjects that they are being observed. However, the act of informing users may cause them to change their behaviour. In longitudinal studies the researcher is reliant on the participant self-reporting issues and behaviour, something which they are not always qualified to do effectively.

Recruitment for the persona interviews and usability testing posed a challenge not only in finding enough people but also the right type of people. Users from a range of backgrounds and differing levels of exposure to AquaBrowser who fulfil the role of one of the personas could be potentially difficult and time-consuming to fulfil. As it turned out, recruitment of staff (excluding librarians) proved to be difficult and was something that we did not manage to successfully overcome.

Established practice

Resource discovery services for libraries have evolved significantly. There is an increasing use of dynamic user interface. Faceted searching for example provides a “navigational metaphor” for boolean search operations. AquaBrowser is a leading OPAC product which provides faceted searching and new resource discovery functions in the form of their dynamic Word Cloud. Early studies have suggested a propensity of faceted searching to result in serendipitous discovery, even for domain experts.

Closer to home, The University of Edinburgh library have conducted usability research earlier this year to understand user’s information seeking behaviour and identify issues with the current digital service in order to create a more streamlined and efficient system. The National Library of Scotland has also conducted a website assessment and user research on their digital library services in 2009. This research included creating a set of personas. Beyond this, the British Library are also in the process of conducting their own user research and persona creation.

The LMS advantage

Creating a set of library personas benefits the University of Edinburgh and the wider JISC community. The characteristics and information seeking behaviour outlined in the personas have been shown to be effective templates for the successful recruitment of participants for user studies. They can also help shape future developments in library services when consulted during the design of new services. The persona hypothesis can also be carried to other institutes who may want to create their own set of personas.

The usability test report highlights a number of issues, outlined in Conclusions and Recommendations, which the university, AquaBrowser and other institutions can learn from. The methodology outlined in the report also provides guidance to those conducting usability testing for the first time and looking to embark on in-house recruitment instead of using external companies.

Key points for effective practice

- To ensure realism of tasks in usability testing, user-generated tasks should be created with each participant.

- Involve as many stakeholders as possible. We did not succeed in recruiting academic staff and were therefore unable to evaluate this user group however, the cooperation with Information Services through project member Liza Zamboglou did generate positive collaboration with the library during the contextual enquiry, persona interviews and usability testing.

- Findings from the user research and usability testing suggest that resource discovery services provided by AquaBrowser for UoE can be improved in order to be useful and easy to operate.

- Looking back over the project and the methods used to collect user data we found that contextual enquiry is a very useful method of collecting natural user behaviour when used in conjunction with other techniques such as interviews and usability tests.

- The recruitment of participants was successful despite the risks highlighted above. The large number of respondents demonstrated that recruitment of students is not difficult when a small incentive is provided and can be achieved at a much lower cost than if a professional recruitment company had been used.

- It is important to consider the timing of any recruitment before undertaking a user study. To maximise potential respondents, it is better to recruit during term time than between terms or during quieter periods. Although the response rate during the summer was still sufficient for persona interviews, the response rate during the autumn term was much greater. Academic staff should also be recruited separately through different streams in order to ensure all user groups are represented.

Conclusions and recommendations

Overall the project outcomes from each of the objectives have been successfully delivered. The user research provided a great deal of data which enabled a set of personas to be created. This artifact will be useful to UoE digital library by providing a better understanding of its users. This will come in handy when embarking on any new service design. The process undertaken to create the personas was also fully documented and this in itself is a useful template for others to follow for their own persona creation.

The usability testing has provided a report (Project Posts and Resources) which clearly identifies areas where the AquaBrowser catalogue can be improved. The usability report makes recommendations that if implemented has potential to improve the user experience of UoE AquaBrowser. Based on the findings from the usability testing and contextual enquiry, it is clear that the contextual issue and its position against the other OPAC (Classic) must be resolved. The opportunity for UoE to add additional services such as an advanced search and bookmarking system would also go far in improving the experience. We recommend that AquaBrowser and other institutes also take a look at the report to see where improvements can be made. Evidence from the research found that the current representation of the Word Cloud is a big issue and should be addressed.

The personas can be quantified and used against future recruitment and design. All too often users are considered too late in a design (or redesign and restructuring) process. Assumptions are made about ‘typical’ users which are based more opinion than in fact. With concrete research behind comprehensive personas it is much easier to ensure that developments will benefit the primary user group.

Additional information

Project Team

- Boon Low, Project Manager, Developer, boon.low@ed.ac.uk – University of Edinburgh National e-Science Centre

- Lorraine Paterson, Usability Analyst, l.paterson@nesc.ac.uk – University of Edinburgh National e-Science Centre

- Liza Zamboglou, Usability Consultant, liza.zamboglou@ed.ac.uk – Senior Manager , University of Edinburgh Information Services

- David Hamill, Usability Specialist, web@goodusability.co.uk – Self-employed

Project Website

- Aggregation of project blogs: http://pipes.yahoo.com/pipes/pipe.run?_id=5c4f2c6809c9b91018d8e74eb2dfd366

- Project Wiki: https://www.wiki.ed.ac.uk/display/UX2/AquaBrowserUX

PIMS entry

Project Posts and Resources

Project Plan

- AquabrowserUX project IPR

- User Study of AquaBrowser and UX2.0

- Usefulness of Project Outputs (Studies, UCD)

- AquabrowserUX Project Budget

- AquabrowserUX Project Team and User Engagement

- AquabrowserUX Projected Timeline, Work plan and Project Methodology

Conference Dissemination

User Research and Persona Development (Obj1)

- Persona Creation: Data Gathering Evaluation

- User Research and Persona Creation Part 1: Data Gathering Methods

- User Research and Persona Creation Part 2: Segmentation – Six Steps to our Qualitative Personas

- User Research and Persona Creation Part 3: Introducing the Personas

- Audio files from each participant interview [link forthcoming once sound files are converted to suitable format]

- Personas: http://bit.ly/digitallibrarypersonas

Usefulness of Resource Discovery Services (Obj2)

Usability of Resource Discover Services (Obj3)

- Recruitment evaluation and screening for personas

- Realism in testing with search interfaces

- Usability Test Report – The University of Edinburgh AquaBrowser by David Hamill http://bit.ly/aquxusabilityreport

- Usability testing highlight videos (x3):

AquabrowserUX Final Project Post

- Final Project Post (this blog post)

When carrying out usability studies on search interfaces, it’s often better to favour interview-based tasks over pre-defined ‘scavenger-hunt’ tasks. In this post I’ll explain why this is the case and why you may have to sacrifice capturing metrics in order to achieve this realism.

In 2006, Jared Spool of User Interface Engineering wrote an article entitled Interview-Based Tasks: Learning from Leonardo DiCaprio in it he explains that it often isn’t enough to create test tasks that ask participants to find a specific item on a website. He calls such a task a Scavenger-Hunt task. Instead he introduces the idea of interview-based tasks.

When testing the search interface for a library catalogue, a Scavenger Hunt task might read:

You are studying Russian Literature and your will be reading Leo Tolstoy soon. Find the English version of Tolstoy’s ‘War and Peace’ in the library catalogue.

I’ll refer to this as the Tolstoy Task in this post. Most of your participants (if they’re university students) should have no trouble understanding the task. But it probably won’t feel real to any of them. Most of them will simply type ‘war and peace’ into the search and see what happens.

Red routes

The Tolstoy Task is not useless, you’ll probably still witness things of interest. So it’s better than having no testing at all.

But it answers only one question – When users know the title of the book, author and how to spell them both correctly, how easy is it to find the English version of Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace?

A very specific question like this can still be useful for many websites. For example a car insurance company could ask – When the user has all of his vehicle documents in front of him, how easy is it for them to get a quote from our website?

Answering this question would give them a pretty good idea of how well their website was working. This is because it’s probably the most important journey on the site. Most websites have what Dr David Travis calls Red Routes – the key journeys on a website. When you measure the usability of a website’s red routes you effectively measure the usability of the site.

However many search interfaces such as that for a university library catalogue, don’t have one or two specific tasks that are more important than any others. It’s possible to categorise tasks but difficult to introduce them into a usability test without sacrificing a lot of realism.

Interview-based tasks

The interview-based task is Spool’s answer to the shortfalls of the Scavenger Hunt task. This is where you create a task with the input of the participant and agree what successful completion of the task will mean before they begin.

When using search interfaces, people often develop search tactics based upon the results they are being shown. As a result they can change tactics several times. They can change their view of the problem based upon the feedback they are getting.

Whilst testing the Aquabrowser catalogue for the University of Edinburgh, participants helped me to create tasks that I’d never have been able to do so on my own. Had we not done this, I wouldn’t have been able to observe their true behaviour.

One participant used the search interface to decide her approach to an essay question. Together we created a task scenario where she was given an essay to write on National identity in the work of Robert Louis Stevenson.

She had decided that the architecture in Jekyll and Hyde whilst set in London, had reminded her more of Edinburgh. She searched for sources that referred to Edinburgh’s architecture in Scottish literature, opinion on architecture in Stevenson’s work and opinion on architecture in national identity.

The level of engagement she had in the task allowed me to observe behaviour that a pre-written task would never have been able to do.

It also made no assumptions about how she uses the interface. In the Tolstoy task, I’d be assuming that people arrive at the interface with a set amount of knowledge. In an interview-based task I can establish how much knowledge they would have about a specific task before they use the interface. I simply ask them.

Realism versus measurement

The downside to using such personalised tasks is that it’s very difficult to report useful measurements. When you pre-define tasks you know that each participant will perform the same task. So you can measure the performance of that task. By doing this you can ask “How usable is this interface?” and provide an answer.

With interview-based tasks this is often impossible because the tasks vary in subject and complexity. It’s often then inappropriate to use them to provide an overall measure of usability.

Exposing issues

I believe that usability testing is more reliable as a method for exposing issues than it is at providing a measure of usability. This is why I favour using interview-based tasks in most cases.

It’s difficult to say how true to life the experience you’re watching is. If they were sitting at home attempting a task then there’d be nobody watching them and taking notes. Nobody would be asking them to think aloud and showing interest in what they were doing. So if they fail a task in a lab, can you be sure they’d fail it at home?

But for observing issues I feel it’s more reliable. If participants misunderstand something about the interface in a test, you can be fairly sure that someone at home will be making that same misunderstanding.

And it can never hurt to make something more obvious.

- In: AquaBrowserUX | Evaluation | inf11 | jisclms | UX2

- 1 Comment

Now that the usability testing has been concluded, it seemed an appropriate time to evaluate our recruitment process and reflect on what we learned. Hopefully this will provide useful pointers to anyone looking to recruit for their own usability study.

Recruiting personas

As stated in the AquabrowserUX project proposal (Objective 3), the personas that were developed would help in recruiting representative users for the usability tests. Having learned some lessons from the persona interview recruitment, I made a few changes to the screener and added a some new questions. The screener questions can be seen below. The main changes included additional digital services consulted when seeking information such as Google|Google Books|Google Scholar|Wikipedia|National Library of Scotland and an open question asking students to describe how they search for information such as books or journals online. The additional options reflected the wider range of services students consult as part of their study. The persona interviews demonstrated that these are not limited to university services. The open question had two purposes; firstly it was able to collect valuable details from students in their own words which helped to identify which persona or personas the participant fitted. Secondly it went some way to revealing how good the participant’s written English was and potentially how talkative they are likely to be in the session. Although this is no substitute for telephone screening, it certainly helped and we found that every participant we recruited was able to talk comfortably during the test. As recruitment was being done by myself and not outsourced to a 3rd person, this seemed the easiest solution at the time.

When recruiting personas the main things I was looking for was the user’s information seeking behaviour and habits. I wanted to know what users typically do when looking for information online and the services they habitually use to help. The questions in the screener were designed to identify these things while also differentiate respondents into one type of (but not always exclusive) persona.

Screener Questions

The user research will be taking place over a number of dates. Please specify all the dates you will be available if selected to take part

26th August |27th August | 13th September | 14th September

What do you do at the university?

Undergraduate 1st |2nd |3rd | 4th | 5th year| Masters/ Post-graduate | PhD

What is your program of study?

What of the following online services do you use when searching for information and roughly how many hours a week do you spend on each?

Classic catalogue | Aquabrowser catalogue | Searcher | E-journals | My Ed | Pub Med | Web of Knowledge/Science | National Library of Scotland | Google Books | Google Scholar | Google | Wikipedia

How many hours a week do you spend using them?

Never|1-3 hours|4-10 hours|More than 10 hours

How much time per week do you spend in any of Edinburgh University libraries?

Never|1-3 hours|4-10 hours|More than 10 hours

Tell me about the way you search for information such as books or journals online?

Things we learned

There were a number of things that we would recommend to do when recruiting participants which I’ve listed below:

- Finalise recruitment by telephone, not email. Not surprisingly, I found that it’s better to finalise recruitment by telephone once you have received a completed screener. It is quicker to recruit this way as you can determine a suitable slot and confirm a participant’s attendance within a few minutes rather than waiting days for a confirmation email. It also provides insight into how comfortable the respondent is when speaking to a stranger which will affect the success of your testing.

- Screen out anyone with a psychology background. It is something of an accepted norm amongst professional recruitment agencies but something which I forgot to include in the screener. In the end I only recruited one PhD student with a Masters in psychology, so did not prove much of a problem in this study. Often these individuals do not carry out tasks in the way they would normally do, instead examining the task and often trying to beat it. This invariably can provide inaccurate results which aren’t always useful.

- Beware of participants who only want to participate to get the incentive. They will often answer the screener questions in a way they think will ensure selection and not honestly. We had one respondent who stated that they used every website listed more than 10 hours a week (the maximum value provided). It immediately raised flags and consequently that person was not recruited.

- Be prepared for the odd wrong answer. On occasion, we found out during the session that something the participant said they had used in the past they hadn’t seen before and vice versa. This was particularly tricky because often students aren’t aware of Aquabrowser by name and are therefore unable to accurately describe their use of it.

Useful resources

For more information on recruiting better research participants check out the article by Jim Ross on UX Matters: http://www.uxmatters.com/mt/archives/2010/07/recruiting-better-research-participants.php. There is also a similarly useful article by Abhay Rautela on Cone Trees with tips on conducting your own DIY recruitment for usability testing: http://www.conetrees.com/2009/02/articles/tips-for-effective-diy-participant-recruitment-for-usability-testing/.

Have I missed anything? If there is something I’ve not covered here please feel free to leave a comment and I’ll make sure I respond. Thanks

- In: AquaBrowserUX | inf11 | UX2

- 1 Comment

In this final part of the persona creation series I will introduce the personas we created and discuss how we plan to keep the personas relevant and current. As mentioned in the previous blog, we created 4 personas based on our interviews. These personas were:

| Pete, the progressive browser |  |

| Badaal, the search butterfly |  |

| Eve, the e-book reader |

|

| Sandra, the search specialist |  |

Full details of each persona can now be viewed on the project wiki. It is also possible to download a Word version of the personas from the Wiki if required.

Looking at the full personas in the wiki, there a few features of them worth mentioning:

- We decided to recreate some of the scales we used when segmenting the groups. We felt that this provided a quick snapshot of the persona in addition to the more descriptive background which hopefully brought the persona to life.

- We used photos from iStockphoto.com and http://www.sxc.hu/

- In addition to background and demographic information we also added sections including Personal Goals, Frustration & Pain Points, Typical Tasks and Information Seeking Behaviour. These were based on the categories we used when writing summaries for each participant.

- We tried to create an alliteration of the persona’s name and their characteristic behaviour to make them more memorable e.g. Pete the progressive browser

Dissemination and future-proofing personas

In addition to publicising the personas through the blogging streams (WordPress and twitter), we have tried where possible to include as much raw data and project documentation as possible on the project wiki. As mentioned in part 1, we had difficulty recruiting staff and consequently were unable to create a persona which represented them. If it’s possible to conduct interviews with University staff members in future projects, an additional persona for staff could be added to the collection. By providing as much raw data as possible in addition to full explanations of the methods used, it should be possible for other groups to create their own personas using the same template.

During this year’s UPA Conference in Munich a presentation on mobile personas highlighted the importance of making them forward thinking. The presentation discussed the dangers of personas becoming outdated and the consequences of this on product design. This is not just important in mobile design, outdated personas are potentially dangerous and could have a negative rather than positive impact on a project. Tom Allison presents a number of ways that personas can become outdated or ‘Zombies’ in his excellent presentation, UX in the Real World: There’s no such thing as “No Persona” (see descriptions below). Reflecting on the process we have taken to create our personas, I am confident that our personas are not zombies, however that is not to say that they cannot ‘be turned’ in the future. To guard against this possibility it is important to encourage others to continue the work, adding more interviews and details appropriate to their work in order to make them appropriate. In our project we were interested in the persona’s attitude to UoE Aquabrowser and Voyager catalogues. However, the information seeking behaviour of each persona is much more general and has the potential to be used as a basis for other academic library use-cases. Providing a thorough account of how the personas were created should hopefully make it easier for others to create their own set of system-specific personas.

Descriptions of the different types of Zombie Personas by Tom Allison:

Mirror Personas: These are the end-user models that get used in the absence of any other reference or description. Anyone on the project team that needs to make a design decision simply asks themselves what they would want in that situation (i.e., they metaphorically look in the mirror). Usually that is not a very good reflection of what the targeted end-user would actually want. Often the difference in these two perspectives can render a result anywhere from terribly frustrating to completely useless to the eventual end-users.

Undead Personas: These are personas that were in fact constructed at one point in a project but that are no longer truly “alive” to the project. They may be hanging on the design team’s wall, or sitting in a report somewhere online or in a drawer. They exist (that’s the “undead” part), but they exert none of the positive effects that a “good persona” can. They may be the worst sort of persona in that they give the team the false confidence that they have “done personas” and they are probably most responsible for the bad reputation that personas sometimes have – in that, the team “did personas” but “it was a waste of time” because they did not keep them alive to the overall process in order to reap the benefits of their work.

Unicorn/Frankenstein Personas: These are personas dreamed up or slapped together from pre-existing parts by someone in the project team. Regardless of how they are used, the signal they give is not a true one. They no more reflect the actual end-user than the programmers mirror persona does and team members who understand that they are based on nothing more than someone’s imagination tend to resent them rather than view them as a resource. The don’t work like good personas and they are resented by those in the know. These along with their undead brethren lead to many with limited experience with personas to have a negative impression of them.

Stupid User Personas: These are perhaps the hardiest of the zombie personas. If personas are built or even just thought about and kept out of the “light of collaborative day” – that is, are not shared and publicized widely and integrated into every stage of a process – then they tend toward negative or dismissive models of the end-user. Teams whose only access to the end-user is a combination of direct communication, interruption and negative feedback to their delivered product are very likely to cultivate these personas in the absence of “good personas”.

Conclusions and reflections

It’s difficult to be subjective when evaluating the success of personas you were involved in creating, particularly because the personas have only just been created. Feedback from others will hopefully provide one way to measure their success. The realism and believability of the personas is important and something I believe we have managed to achieve but I am always interested to know if others agree and if there are any improvements we could make. Having spent a little time working with some* of the personas to recruit participants for the usability testing of Work package 3 (Objective 3) I have made some observations:

There are not huge differences between Baadal and Eve. The differentiating factors are the consumption of digital resources (e.g e-books) and use of the University digital libraries. On many other scales they are the same or very similar. This has made it a little trickier to recruit to each persona as often the details provided by willing participants makes them difficult to categorise as one or the other. This evidence provides a compelling argument that these personas could be merged. However, there is also an argument that participants do not have to fit neatly into one persona or another. For the purpose of the project we will continue to use three individual personas. It will be possible to evaluate the success of the personas over the course of time.

* Findings from the interviews led to the decision to test with students as these are the primary target audience for UoE Aquabrowser. Consequently we used personas Pete, Badaal and Eve in recruitment.

User Research and Persona Creation Part 2: Segmentation – Six steps to our Qualitative Personas

Posted on: August 30, 2010

- In: AquaBrowserUX | inf11 | UX2

- 2 Comments

In Lorraine’s last blog she described the data gathering methods used to obtain representative data from users of Edinburgh University’s Library services, the purpose of which was to identify patterns in user behaviours, expectations and motivations to form the basis of our personas. Raw data can be difficult to process and it is impossible to jump from raw notes to finished persona in one step, hence our six step guide.

There is no one right way to create personas and it depends on a lot of things, including how much effort and budget you can afford to invest. There are lots of articles on the web detailing various approaches and after much reading we decided to rely on 2 main sources of information which we felt best suited our needs.

One resource was the Fluid Project Wiki which is an open, collaborative project to improve the user experience of community source software and provides lots of useful guidance as well as sample personas. The other resource which we heavily relied on throughout the whole process was Steve Mulder’s book The User Is Always Right: A Practical Guide to Creating and Using Personas for the Web, which contains lots of great advice as well as step-by-step coverage on user segmentation.

There are three primary approaches to persona creation, based on the type of research and analysis performed:

- Qualitative personas

- Qualitative personas with quantitative validation

- Quantitative personas

There are a number of important steps to go through in order to get from raw data to personas and I will now explain the tools and methods used to generate our segments and personas for anyone who wishes to follow in our footsteps.

The first thing we did was to plan out a schedule of work which consisted of the following:

- Review and refine interview notes in the project wiki and flesh out user goals

- Write summaries for each of the participants

- Do a Two by Two comparison, to identify key similarities/differences

- Identify segments

- Write the personas

- Review personas

Step 1: Review/refine notes

We spent a day reviewing our notes in the wiki and fleshing out goals by referring to written notes taking during each interview, checking the audio recordings where necessary. We worked as a team which was beneficial as we were both present for each interview and therefore had a good grasp of all the data in front of us. Once we were happy with our set of notes, we printed out participant’s interview notes and attached each to the white board to make it easier to review all data grouped together.

We spent a day reviewing our notes in the wiki and fleshing out goals by referring to written notes taking during each interview, checking the audio recordings where necessary. We worked as a team which was beneficial as we were both present for each interview and therefore had a good grasp of all the data in front of us. Once we were happy with our set of notes, we printed out participant’s interview notes and attached each to the white board to make it easier to review all data grouped together.

Step 2: Summarise participants

Next step was to summarise each of our 17 participants (try to figure out who are these people) based on the following 4 categories.

Next step was to summarise each of our 17 participants (try to figure out who are these people) based on the following 4 categories.

- Practical and personal goals

- Information seeking behaviour

- How they relate to library services

- Skills, abilities and interests

We used different coloured post-it notes to denote each of the above categories. Once we had gone through this process for each participant, our whiteboard was transformed into a colourful mirage of notes.

We were now ready to start a two-by-two comparison of participants.

Step 3: Two-by-Two Comparisons

The next step utilised the two-by-two comparison method, a technique advocated by Jared Spool at User Interface Engineering (UIE.com). This works by reading 2 randomly chosen participant summaries and listing attributes that make the participants similar and different. We then replaced one of the summaries with another randomly chosen one and repeated the process until all summaries were read.

Below is a list of some of the distinctions identified between our participants, using this method:

- Type of library user

- Years at Edinburgh University

- Use of Edinburgh University library resources (digital and physical)

- Use of external resources

- System Preference (Classic or Aquabrowser)

- Attitude to individual systems

- Information seeking behaviour

We then created a scale for each distinction identified during the two-by-two comparison and determined end points. Doing so allowed us to place each participant on the scale and directly compare them. Most variables can be represented as ranges with two ends. It doesn’t matter whether a participant is a 7 or 7.5 on the scale; but what matters is where they appear relative to other participants. The image below provides an example of our 12 scales mapped for each of our 17 participants.

We then created a scale for each distinction identified during the two-by-two comparison and determined end points. Doing so allowed us to place each participant on the scale and directly compare them. Most variables can be represented as ranges with two ends. It doesn’t matter whether a participant is a 7 or 7.5 on the scale; but what matters is where they appear relative to other participants. The image below provides an example of our 12 scales mapped for each of our 17 participants.

Step 4: Identify Segments

Now that we had all our participants on the scales, we then colour coded each individual to make it easier to identify groupings of participants on each of the scales. We looked for participants who were grouped closely together across multiple variables. Once we found a set of participants clustering across six or eight variables, we saw this as a major behaviour pattern which formed the basis of a persona.

Now that we had all our participants on the scales, we then colour coded each individual to make it easier to identify groupings of participants on each of the scales. We looked for participants who were grouped closely together across multiple variables. Once we found a set of participants clustering across six or eight variables, we saw this as a major behaviour pattern which formed the basis of a persona.

After quite a bit of analysis, we identified 6 major groupings, each identifying an archetype / persona, which we gave a brief description to on paper, outlining the characteristics and identifying their unique attributes.

After reviewing each description we realised that group 6 was very similar to group 4 and so merged these two sets together, leaving 5 groups at the end of this step.

After reviewing each description we realised that group 6 was very similar to group 4 and so merged these two sets together, leaving 5 groups at the end of this step.

When carrying out this step, it is important to remember that your groups should:

- explain key differences you’ve observed among participants

- be different enough from each other

- feel like real people

- be described quickly

- cover all users

Step 5: Write the Personas

We were now ready to write up our 5 personas. For each group we added details around the behavioural traits based on the data we had gathered, describing their goals, information seeking behaviours and system usage amongst other things. We also talked about frustrations and pain points as well as listing some personal traits to make them feel more human.

We gave each persona a name and a photo which we felt best suited their narrative. We tried to add parts of participant’s personalities without going overboard as this would make the persona less credible. We kept the detail to one page and based it on a template provided by the Fluid Project wiki. It’s important to keep persona details to one page so they can be referred to quickly during any discussions. Remember that every aspect of the description must be tied back to real data, or else it’s shouldn’t be included in the persona.

Some people prefer to keep their persona details in bullet points, but we felt that a narrative would be far more powerful in conveying each of our persona’s attitudes, needs and problems. We also added a scale to each persona, detailing their behaviour and attitudes, which serves as a visual summary of the narrative and main points. It may be useful to refer to Fluid Persons Format page for example of these templates: http://wiki.fluidproject.org/display/fluid/Persona+Format

Step 6: Review the Personas

Once our personas were written, we reviewed them to ensure they had remained realistic and true to our research data. We felt that 2 personas in particular had more similar behaviours and goals than differences so we merged them into one complete persona. This left us with 4 library personas representing the students and librarians who were interviewed:

- Eve the e-book reader: “I like to find excerpts of books online which sometimes can be enough. It saves me from having to buy or borrow the book.”

- Sandra the search specialist: “In a quick-fire environment like ours we need answers quickly”

- Pete the progressive browser: “Aquabrowser and Classic, it’s like night and day”

- Baadal the search butterfly: “Classic is simple and direct but Aquabrowser’s innovative way of browsing is also good for getting inspiration.”

A full description of the personas can be found on the persona profiles page of our project wiki: https://www.wiki.ed.ac.uk/display/UX2/persona+profiles

Research has shown that a large set of personas can be problematic as the personas all tend to blur together. Ideally, you should have only the minimum number of personas required to illustrate key goals and behaviour patterns, which is what we ended up with. Finally, to ensure we had a polished product, we asked a colleague who was not involved in the persona creation, to review the personas for accuracy in spelling and grammar.

Conclusion

From my experience, I would say that the most difficult step of the process was getting from step 3 (Two by Two comparison) to step 4 (Identify segments). Although we had initially planned to spend 3 days creating our personas, in the end it took us 5+ days. If we were to repeat this exercise, I would allocate adequate time directly after each individual interview to write up detailed notes on the interviewee, detailing their specific goals, behaviours, attitudes and information seeking behaviour, rather than waiting until a later date to review all the notes together, as described in Step 2. In saying this, there are various different approaches which can be taken when creating personas and we would be very interested to learn what other researchers might do with the same data.

In the concluding part of this blog series, “User Research and Persona Creation Part 3: Introducing the personas”, Lorraine will discuss how we plan to keep the personas relevant and current in the future.

- In: AquaBrowserUX | User Research | UX2

- 10 Comments

In a previous blog I evaluated the progress of the data gathering stage of persona creation for both Aquabrowser UX and UX2.0. As the data gathering has now been completed and analysed, we have the beginnings of our personas. It therefore seemed a good time to reflect on the process as well as document and review our methods. In the first of three blogs detailing our persona creation, I will first talk about the data gathering methods and reflect on its success.

Originally the plan had been to create personas by conducting qualitative research and validating the segments with quantitative data. Unfortunately we underestimated the time taken and resources required to conduct the qualitative research and as such were unable to validate the personas using quantitative research. Although this approach is good when you want to explore multiple segmentation models and back up the qualitative findings with quantitative data, personas created without this extra step are still valid and extremely useful. As this is the first time the team has conducted persona data gathering, it took longer to do than anticipated. Coupled with the restrictions on time and budget for this project, the additional validation was always an ambition. I’ve stepped through the process we used below to allow others to adopt it if needed. The process is a good template for conducting all types of interviews and not just to create personas.

1. Designing the interviews

When designing the interview questions the team first set about defining the project goals. This was used as a basis for the interview questions and also helped to ensure that the questions covered all aspects of the project goals.

Goal 1: In relation to University of Edinburgh digital library services, and AquaBrowser, identify and understand;

- User general profiles (demographic, academic background, previous experiences)

- User behaviours (e.g. information seeking) / use patterns

- User attitudes (inc. recommendations)

- User goals (functional, fit for purpose)

- Data, content, resource requirements

To keep the interview semi-structured and more conversational, the questions created were used primarily as prompts for the interviewer and to ensure that the interviewees provided all the information being sought. More general questions were posed as a springboard for more open discussion. Each question represented a section of discussion with approximately six questions in total. Each question in turn had a series of prompts. The six opening questions are detail below:

- Could you tell me a bit about yourself…?

- Thinking now about how you work and interact with services online, what kind of activities do you typically do when you sit down at the computer

- I want to find out more about how you use different library services, can you tell me what online library services you have used?

- We want to know how you go about finding information…What strategy do you have for finding information?

- Finally, we’d like to ask you about your own opinions of the library services.. a. What library or search services are you satisfied with and why? b. Why do you choose <mentioned services> over other services?

Interviewees were also given the opportunity at the end of the interview to add anything they felt was valuable to the research or which they just wanted to get off their chest. Several prompt question were modified or added to the librarian interview script, otherwise the overall scripts were very similar

When the interview was adapted into a script for the interviewer, introductory and wrap-up sections were added to explain the purpose of the interview and put the interviewees at ease. These sections also provided prompts to the interviewer to ensure permission was obtained beforehand and that the participant was paid at the end.

2. Piloting the interview

The script was piloted on a colleague not involved in the project a few days before the interviews began. This provided an opportunity to tweak the wording of some of the questions so they were clearer, time the interview to ensure it could be conducted in approximately 45 minutes and also help the team to become more familiar with the questions and prompts. Necessary changes were consequently made to the script to be used for the first ‘real’ interview.

3. Recruitment – Creating a screener

In order to recruit a range of users at the university, a screener was devised. This would provide information on each participant’s use patterns and some basic demographic details. It also allowed us to find out the availability of each participant as the interviews were intended to be conducted over a four-week period in June and July. It also made it easier to collect contact details from users who had already agreed to take part. As with most user research where incentives are involved, there is always the danger that participants will be motivated by the reward of payment and consequently will say whatever they need to say in order to be selected. As we were looking for users who were familiar with Aquabrowser and Voyager (The ‘Classic’ catalogue), we disguised these questions among other library services. This prevented the purpose of the research from being exposed to the participant. The screener questions we used are detailed below:

Screener questions:

- Please confirm if you are willing to take part in a 45 minute interview? Note: There will be a £15 book voucher provided for taking part in an interview.

- In addition to interviews we are also recruiting for website testing sessions (45-60 min). Would you would be interested in taking part?

Note: There will be a £15 book voucher provided for taking part in a website testing session. - What do you do at the university? Undergrad: 1st/2nd/3rd/4th/Post grad/PhD/Library staff/Teaching staff/Research staff/other.

- What is your department or program of study?

- Which of the following online services do you use at the University and how many hours a week do you spend on each? Classic catalogue/ Aquabrowser catalogue/Searcher/E-Journal search/ PubMed/ My Ed/Web of Knowledge/Science/Science Direct.

- How much time per week do you spend in any of Edinburgh University libraries? None/Less than 1 hour a week/1-3 hours a week/4-10 hours a week/More than 10 hours a week.

- Please state your prefered mode of contact to arrange interview date/time.

- Please leave your name.

- Please leave relevant contact details: Email and/or telephone number.

Thank you very much for your time. If you are selected to participate in the current study, we’ll be in touch to see when would be the best time for your session.

4. Recruitment – Strategy

A link to the screener was publicised through a variety of streams. An announcement was created and placed in the MyEd portal which every person within the university has access to (staff and students). In addition to this, an event was created which was also visible within the events section of MyEd. Several email invitations were sent via mailing lists requesting participation. These lists included the School of Physics, Divinity and Information Services staff.

To encourage students and staff to participate an incentive was provided. A £15 book voucher was promised to those who agreed to take part in an interview. The screener was launched on 21st May and ran until the interviews were completed on 15th July. Interviews were scheduled to take place over four weeks which began on 17th June. Six interviews were carried out on average each week, taking place over two separate days. These days varied, but often took place on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Fridays. This was influenced by the availability of team members to carry out the interviews. Each participant was given the opportunity to name their preferred location for the interview. Those interviews that can take place in the user’s own environment are more likely to put the participant at ease and consequently produce better interviews. However, every participant ended up opting to meet at a mutually convenient location – the main library. This public venue is familiar to all participants and centrally located making it less intimidating and easy to find. It also enabled more interviews to be conducted over a short period of the day as travelling to various locations was not required.

Participants were recruited based on a number of factors. Their position in the university (student, staff etc.), their familiarity (or in some cases not) with library services, especially Aquabrowser and Voyager (Classic catalogue). Individuals who spent a reasonable amount of time using these services were of interest but a number of individuals who did not spend much time using the services were also recruited to provide comparisons. Obviously their availability was also an important factor and anyone who was not available in June and/or July were excluded.

Although the screener speeded up the recruitment process, there was still a number of individuals on the list who did not respond to additional email requests to participate. This is always frustrating when people have apparently registered their interest when completing the screener. Despite this we managed to recruit 19 participants from a list of 82 respondents which was approximately a 23% response rate. Unfortunately from these 19 individuals, two individuals dropped out at the last-minute. One person did not show up and another cancelled due to ill-health. As these cancellations occurred on the last day of interviews and did not represent a under-represented demographic group, the decision was taken not to recruit replacements and to conclude the data gathering stage with 17 participants.

Unfortunately there were some groups who were under-represented. The biggest concern was the limited number of staff and in particular, lecturers in the study. This ultimately meant that this group could not be adequately analysed. Time limitations meant it was difficult to undertake additional strategies to target these individuals. The data gathered was only able to provide personas representing those interviewed and consequently a persona for faculty staff was not possible. Any future persona development work should ensure that a variety of lecturers and researchers are interviewed as part of the process.

5. Conducting the interviews

Before the interviews began, several preparations had to be made. Booking audio recording equipment, sourcing a digital camera for images and creating consent forms for both audio and visual documentation was done. Two team members were present for every interview. One would take notes while the other interviewed the participant. These roles were swapped for each new interview, giving both team members the chance to be both interviewer and note-taker. After discussing how best to take notes it was decided that having a printed template for each interview which the note-taker could complete would be a good strategy. This would help to keep notes in context as much as possible and make the note-taking process as efficient as possible. Doing so removes the danger of important information being lost. The note-taker would also record time stamps each time something ambiguous or important was said so that clarification could be made later by listening to the recordings.

After each interview the team transferred the notes onto the project Wiki. Doing so allowed a post-interview discussion to take place where both members reflected on their understanding of the interviewees comments. It also provided the opportunity to review the interview and discuss improvements or changes that could be made to the next one. This was particularly useful for the first few interviews.

Having two team members present for each interview was time-consuming but also provided many benefits. During the interview it gave the interviewer a chance to consult with someone else before concluding the interview. Often the note-taker may have noted something the interviewer overlooked and this time at the end ensured that any comments made earlier could be addressed. In addition, any missed questions or prompts were asked at this point. It is also beneficial for all team members to be present when it comes to analysing the data at the end. Individuals do not have to rely heavily on the notes of another to become familiar with the participant. This is particularly important when it is not possible to have transcripts of each interview made. Finally, having a note-taker removes the burden from the interviewer who does not have to keep pausing the interview to note down anything that has been said. As these interviews were intended to be semi-structured and have a discursive feel, having a note-taker was crucial to ensuring that this was achieved.

Conclusion

Overall the interviews were quite successful. However, in future more interviews with staff should be conducted in addition to a web survey so that the segmentation can be validated. Full access to the documents created during the process and the resources consulted throughout can be found on the project Wiki.

In the second part of the series guest blogger, Liza Zambolgou will be discussing the segmentation process and how we analysed all of the data collected from the interviews.

- In: AquaBrowserUX | UX2

- 1 Comment

Iterative evaluation process

Last month saw the project plan and conduct a contextual enquiry as part of the data gathering process for persona development. This field study involved gathering data from Edinburgh University library users in situ. The aims of the exercise was to understand the background of visitors, their exposure to Aquabrowser and their information seeking behaviour.

Two site visits were conducted on the 11th and 12th May in the main library at George Square. In addition to this longer (45 minute) user interviews are scheduled to take place starting in the week beginning 14th June (next week).

Below is a brief evaluation of this research phase. Detailed results will be published in a subsequent blog post.

SWOT analysis:

Strengths:

Recruitment of participants for longer interviews is going well. At last count we had 74 respondents from a selection of backgrounds including undergraduates, post graduates, PhD students, staff and librarians. Participant availability is also spread over June, August and September meaning that recruitment looks achievable.

We have reviewed the timing of the usability testing to take into account the persona work. Testing will now take place in two stages: 1. Aug and 2. Sept to capture data from 1. staff (when university is quiet) and 2. students (to increase availability during freshers week). This strategy will ensure that the persona research can be used effectively to recruit representative users.

By using a variety of resources, a master interview script has been created that will then be altered to suit different groups: students, staff, librarians. The interview will be piloted before the first interview takes place allowing any final changes to be made beforehand. The interviews themselves will be conducted in pairs to begin with, allowing the interviewer to concentrate on their questions while someone else takes rigorous notes. Doing so will also ensure no information is missed.

Weaknesses:

The contextual enquiry approach in the library has been limited by a number of factors. Timing of the exercise meant that meeting a range of library users was difficult. Exams were happening during this time meaning that the main library users were students studying. Consequently these students were very busy, stressed and engrossed in work for a large part of their time in the library. Trying to approach students to interview was therefore limited to those who were wandering around the main foyer. In addition, one of the biggest barriers to observing user behaviour of Aquabrowser was the limited awareness of it among students. Users currently have the choice of two catalogues, Voyager and Aquabrowser. As a result, very few observations of students using Aquabrowser naturally were made.

A diary study has been proposed to complement the library observations and user interviews. However, the limited timescale and budget of the project will make it more difficult to recruit a willing participant. In addition, the level of resources required to run and manage such a study could be difficult as it would be required to run alongside other ongoing work within the project and for the UX2.0 project.

Opportunities:

After meeting with engineer, Meindert from Aquabrowser, several opportunities have presented themselves. There is a real possibility of accessing services not currently implemented by Edinburgh University though a demo site and other University libraries. This will allow us to better understand ‘My Discoveries’ and observe how social services including user-generated ratings and reviews are used. It will be possible to demonstrate these services to University users in order to gauge acceptance of such technology and perhaps create a case for its implementation.

Threats:

Participant cancellations and no shows during interviews are always a threat in user research but with an extensive list of willing and pre-screened participants, finding replacements should not be a problem.

The scope of the project was narrowed after realising that was too wide to be evaluated in full. Narrowing the scope from ‘library in general’ to ‘digital library catalogues’ means the evaluation is more achievable within the timescale.

UPA Conference 2010: Day 2

Posted on: June 3, 2010

- In: AquaBrowserUX | inf11 | UX2

- 6 Comments

Findings from day 2 of the UPA 2010 conference are detailed in the second part of my UPA blog.

Ethnography 101: Usability in Plein Air by Paul Bryan

Studying users in their natural environment is key to designing innovative, break-through web sites rather than incrementally improving existing designs. This session gives attendees a powerful tool for understanding their customers’ needs. Using the research process presented, attendees will plan research to support design of a mobile e-commerce application.

As our AquabrowserUX project contemplates an ethnographic study, this presentation seemed vital to better understanding the methods involved. Paul Bryan provided a very interesting insight into running such studies, explaining when to use ethnography and a typical project structure. The audience also got the chance to plan an ethnographic study using a hypothetical project.

Some basic information that I gathered from the talk is listed below:

What is ethnography?

- It takes place in the field

- It is observation

- It uses interviews to clarify observations

- It pays attention to context and artifacts

- and it utilises a coding system for field notes to help with analysis

Some examples of ethnographic studies include:

- 10 page diary study with 1 page completed by a participant each day

- In home study using observation, interviews and photo montages created by participants to provide perspectives on subjects

- Department store observation including video capture

Ethnography should be used to bring insight into a set of behaviours and answer the research question in the most economical way. It should also be used to:

- Identify fundamental experience factors

- Innovate the mundane

- Operationalize key concepts

- Discover the unspeakable, things which participants aren’t able to articulate themselves

- Understand cultural variations

A proposed structure of an ethnographic project would be as follows:

- Determine research questions or focus

- Determine location and context

- Determine data capture method (this is dependent on question 1)

- Design data capture instruments

- Recruit

- Obtain access to the field

- Set up tools and materials

- Conduct research, including note taking

- Reduce data to essential values

- Code the data

- Report findings and recommendations, including a highlights video where possible

- Determine follow-up research

As I suspected, ethnography is not for the faint hearted (or light pocketed) because it clearly takes a lot fo time and people-power to conduct a thorough ethnographic study. It seems that as a result, only large companies (or possibly academic institutes) get the chance to do it which is a shame because it is such an informative method. For example, all video footage recorded must be examined minute by minute and transcribed. My favourite quote of the session was in response to a question over the right number of participants required for a study. Naturally this depends heavily on the nature of the project. Paul summed it up by comparing it to love: “When you know you just know”. Such a commonly asked question in user research is often a difficult one to answer exactly so I liked this honest answer.

When analysing the data collected Paul suggested a few techniques. Using the transcribed footage, go through it to develop themes (typically 5-10). In the example of a clothes shopping study this may be fit, value, appeal, style, appropriateness etc. Creating a table of quotes and mapping them to coded themes helps to validate the them. He also recommended that you focus on behaviours in ethnography, capture cases at opposite end of the user spectrum, and always look for unseen behaviours.

Designing Communities as Decision-Making Experiences by Tharon Howard and Wendy R. Howard

What can you do when designing an online community to maximize user experience? This presentation, based on two decades of managing successful online communities, will teach participants how to design sustainable online communities that attract and retain a devoted membership by providing them with “contexts for effective decision-making.”

This topic was interesting on a more personal level because it dealt with themes from my MSc dissertation on online customer communities. Tharon has recently published a book on the subject call ‘Design to Thrive’ which sounds really interesting. He and Wendy co-presented their knowledge of online communities detailing why you would create one, the difference between a community and a social network and the different types of users in a community. Their culinary acronym ‘RIBS’ (Renumeration, Influence, Belonging and Significance) provided a heuristic framework with which to follow in creating a successful community.

They pointed out that the main difference between a social network and a community is the shared purpose among members. Normally a community is developed around a theme or subject whereas social networks are created as a platform for individuals to broadcast information of interest to them and not necessarily on one topic. An online community is a useful resource when you want to build one-to-one relationships, share information quickly and easily and create a seed-bed where collective action can grow. I think this is true but that developments in social networks such as groups and categorised information means that social networking sites are beginning to provide communities within their systems.

Back to the RIBS acronym, Tharon talked about renumeration as the first heuristic for community creators. A mantra which he provided is a follows:

The most important renumeration community managers have to offer is the experience of socially constructing meaning about topics and events users wish to understand.

It is important to reward members for giving back to the community as this will reward those members, it will also ensure the continuation of the community through active participation; “It’s a two-way street“. Such rewards can include features that are ‘unlocked’ by active members and mentoring for new members (noobs). Tharon also states that influence in a community is often overlooked by managers. Members need to feel the potential for them to influence the direction of the community to continue to be an active participant. Providing exit surveys, an advisory council, a ‘report a problem’ link and rigorously enforcing published policies will help to ensure influence is incorporated into an online community.

Belonging is apparently often overlooked as well. By including shared icons, symbols or rituals to represent a community allows members to bond through these common values and goals. Including a story of origin, an initiation ritual, levelling up ceremony, and symbols of rank all provide the sense of belonging which is important to a community member.

Significance is the building and maintenance of a community brand for those in the community. It’s a common characteristic of people to want to be part of an exclusive group. The exclusivity seems to increase the desire to join in many cases. By celebrating your community ‘celebrities’ and listing (often well-known) members in a visitor centre section of the community you can allude to its exclusivity. By making it invite only also helps to increase the significance of the community.

Touchdown! Remote Usability Testing in the Enhancement of Online Fantasy Gaming by Ania Rodriguez and Kerin Smollen

This session presents a case study on how ESPN/Disney with the assistance of Key Lime Interactive improved the user experience and increased registrations of their online fantasy football and baseball gaming through the effective use of moderated and automated remote usability studies.

This topic was the first of another series of short (this time 40 minute) presentations. As before, the time limitation often impacted on the detail within each talk. Understandably, speakers struggled to get through everything within the time allocated and either had to rush through slides or had to cut short questions at the end. Unfortunately this happened in the talk by Ania Rodriguez and Kerin Smollen. Although an interesting case of how ESPN (Smollen) have collaborated with Key Lime Interactive (Rodriguez) to conduct remote testing, it was not the type of remote testing I was hoping to learn more about. I already have some experience running an unmoderated test was more interested to hear detail on moderated remote testing. However, I was encouraged to hear that UserZoom came out favourably as the software of choice to run this remote study. I have been interested in using this software for a while and will hopefully get the chance to use it at some point in the future.

Multiple Facilitators in One Study: How to Establish Consistency by Laurie Kantner and Lori Anschuetz

In best practice for user research, a single researcher facilitates all study sessions to minimize variation. For larger studies, assigning one facilitator may miss an opportunity, such as catching select participants or delivering timely results. This presentation provides guidelines, with case study examples, for establishing consistency in multiple-facilitator studies.

Another short presentation which gave advice on how to ensure that consistency is achieved when several facilitators work on a project. It may not seem like rocket science but the best method used to capture information was a spreadsheet with various codes for observations. This document is shared and updated by each facilitator to ensure everything is accurately captured. It’s not a perfect system and often learning lessons and selecting facilitators carefully will help to reduce issues later but it seemed to work well in this case. Where most usability professionals would balk the idea of multiple facilitators which is often considered bad practice, it is too often a necessity in time constrained projects which may even be spread out around the world. Indeed Lauri and Lori suggest that multiple facilitators can bring benefits which includes more than one perspective, as the old proverb goes – ‘two heads are better than one‘!

Creating Richer Personas – Making the Mobile, International and Forward Thinking by Anthony Sampanes, Michele Snyder, Brent White and Lynn Rampoldi-Hnilo

Personas are a great way to get development teams in sync with a new space and their users. This presentation discusses solutions to extending personas to include novel types of information such as mobile behavior, cultural differences, and ways to promote forward thinking.

This 40 minute presentation provided lots of information that was useful to me (and the projects) and that presented new ways of working with personas. However, with additional time it would have been great to go over the data collection methods in more detail as this is something we are currently undertaking in AquabrowserUX.

Traditionally personas are limited to desktop users. However, this is changing as doing things on the move is now possible with the aid of smartphones. The presenters indicated that they found little literature on cross cultural or mobile personas which was a shock. The internationalization of business and development of smartphones is not new so I am surprised that more practitioners have not been striving to capture these elements in their own personas.

The team stated that they observed people to understand how they use smartphones to do new things, key tasks conducted, tools used, context and culture. Shadowing people over a day, surveying them and on the spot surveys, image diaries and interviews with industry people were all used to capture data. The outcome they discovered was that mobile users are different in so many ways to other users they should therefore be considered uniquely. Consequently personas were created that focused on the mobile user, not what they did elsewhere (other personas were used for that purpose). The final personas included a variety of information and importantly, images as well. Sections included ‘About Me’, ‘Work’, ‘Mobile Life’ and ‘My Day’.

In addition to mobile life, cultural differences were integrated throughout the persona. To incorporate a forward-thinking section called ‘Mobile Future’ researchers asked participants what they would want their phone to do in the future that it can’t currently do. This provided an opportunity for the personas to grow and not become outdated too quickly.

I hope the slides are available soon because I would love to read the personas in more detail. Outdated personas has always been a problem and was even discussed by delegates over lunch the day before. It is great to see how one organisation has tried to tackle this issue.

Usability of e-Government Web Forms from Around the World by Miriam Gerver

Government agencies worldwide are turning from paper forms to the Internet as a way for citizens to provide the government with information, a transition which has led to both successes and challenges. This presentation will highlight best practices for e-government web forms based on usability research in different countries.

Unfortunately technical issues impacted to some extend on the final presentation of the day. Fortunately the presenter had the foresight to prepare handouts of the slides which came in very handy. The bulk of the presentation was to provide insights into good and bad practices of government web forms around the globe. Some things that characterise government forms are the legal issues which require certain information to be included. For example a ‘Burden Statement’ must be provided according to US law. A Burden Statement includes information on the expected time to complete the form. Although this information is useful and should be on the page, it’s implementation in the form is not always ideal as other delegates pointed out. Position and labelling means that users may never find this information and consequently be aware that it exists.

I was impressed that some forms are designed with a background colour which matches the paper version as this helps to maintain consistency and avoid confusion. An issue raised in working with paper copies and digital forms is the potential problem of people using both simultaneously or copying work from a paper copy to the online version. By greying out irrelevant questions instead of hiding them, users can follow along with corresponding questions, avoiding potential confusion. I was also surprised to hear that some government forms allow you to submit the form with errors. If the form is important it makes sense that users are encouraged to submit it in any circumstances. However, users are also encouraged to fix errors before submitting the form where possible.

UPA Conference 2010: Day 1

Posted on: June 1, 2010

- In: AquaBrowserUX | inf11 | UX2

- 6 Comments

Below I have provided some insights and experiences from the presentations I attended on the first day of the UPA conference.

Opening Keynote: Technology in Cultural Practice by Rachel Hinman

In the keynote, Rachel shares her thoughts on the challenges and opportunities the current cultural watershed will present to our industry as well as the metamorphosis our field must undergo in order to create great experience across different cultures.

In the opening presentation Rachel recounted her experiences collecting data from countries such as Uganda and India and how her findings impact how we design for different cultures. One of the most interesting points she made was the discovery that people in Uganda don’t have a word for information. People there correlate the term information as meaning news which is the type of information they would be most interested in receiving through their phone. The key message from her presentation was that we the design of technology for cultures other than our own should begin from their point of view. We should not impose our own cultural norms on them. For example, the metaphor of books and libraries is alien to Indians who do not see this icon in their culture on a daily basis. Conducting research similar to that of Rachel’s will help to design culturally appropriate metaphors which can be applied and understood.

Using Stories Effectively in User Experience Design by Whitney Quesenbery and Kevin Brooks

Stories are an effective way to collect, analyze and share qualitative information from user research, spark design imagination and help us create usable products. Come learn the basics of storytelling and leave having crafted a story that addresses a design problem. You’ve probably been telling stories all along – come learn ways to do it more effectively.

This was a great presentation to kick off the conference. Whitney and Kevin were very engaging and talked passionately about the subject. There was lots of hands-on contribution from the audience with a couple of short tasks to undertake with you neighbour (which also provided a great way to meet someone new at the same time). The overriding message from this presentation was the importance of listening; asking a question such as ‘tell me about that‘ and then just SHUT UP and listen! I found this lesson particularly important as I know it’s a weakness of mine. I often have to stop myself from jumping in when a participant (or anyone) is talking, even if just to empathise or agree with them. The exercise in listening to your neighbour speak for a minute without saying a word was very difficult. It’s true that being a good listener is one of the most important lessons you can learn as a usability professional.

Learning to listen and when to speak are key to obtaining the ‘juicy’ information from someone. Often those small throw-away comments are not noticed by the storyteller but if you know how to identify a fragment that can grow into a story you often reveal information which illuminates the data you have collected. Juicy information often surprises and contradicts common beliefs and is always clear, simple and most of all, compelling.